Just because traditional education was a matter of routine in which the plans and programs were handed down from the past, it does not follow that progressive education is a matter of planless improvisation.

– John Dewey

Experience & Education

This post continues a mini-series examining John Dewey’s Experience & Education chapter-by-chapter.

Dewey begins his second chapter with what soon becomes a familiar drum beat – we cannot create a new theory of education simply by defining ourselves as what we are not. Progressives, Dewey points out, are at risk of this if all we manage to do is say, “We are against traditional ways of playing school.”

He then turns his attention to the idea of experiences and clarifies that education based on experience is not an idea unique to progressives. All education is experience. Dewey, in contrast, is calling for a theory of experience that stakes a claim on what experience in education should accomplish, “Any experience is miseducative that has the effect of arresting or distorting the growth of further experience.”

If every classroom (traditional or not) is a site of experience, Dewey argues the importance we must note is the quality of experience which depends on two aspects, “agreeableness or disagreeableness” and “its influence on later learning.”

Again, as in Chapter 1, Dewey takes pains to explain experience is not meant as improvisation or as putting the things and people in a space and hoping what we want to achieve is achieved. This strikes me as humorous given Dewey was writing Experience & Education as a reflection and attempt to right the course of progressive education. Decades later, we’re misinterpreting progressive teaching in the same ways.

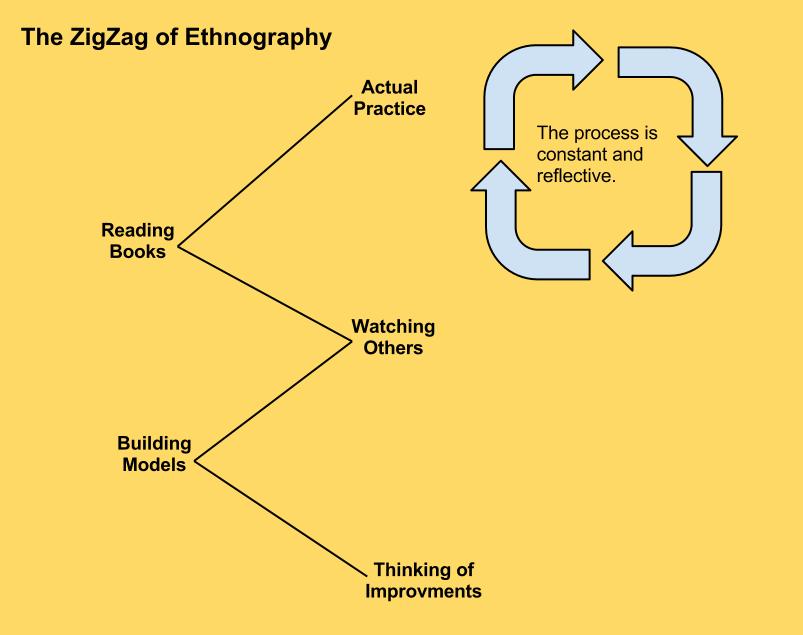

Here too, Dewey acknowledges the difficulty of progressive education compared to traditional schooling. Traditional schools could plug along, doing a variation today of what they did yesterday. Progressive schools, in crafting experiences need both a theory and a critical eye for how to implement that theory.

As is so often the case, the work worth doing is the more difficult work.

Progressive education is simple, Dewey admits, but that should not be confused with easy, “[A] coherent theory of experience, affording positive direction to selection and organization of appropriate educational methods and materials, is required by the attempt to give new direction to the work of the schools. The process is a slow and arduous one. It is a matter of growth and there are many obstacles, which tend to obstruct growth and to deflect it into wrong lines.”

Anyone who has ever worked within a progressive school knows this to be true. On the worst days, the struggle to re-invent schooling in a way that remains aligned with progressive philosophy can result in traditional schooling and their neo-traditional counterparts appearing appealing if for no other reason than their ease. On the best days, though, connecting students with learning experiences structured and based on the wells of knowledge provided by teachers and communities can fill the progressive experience with an undeniable sense of purpose and worth.

Still, though, this chapter reminds us of the dangers of a good idea in vague minds. Dewey closes with a prescient warning of attacks of traditionalists on progressive ideals and what must be done to rebuff those attacks:

[E]ducational reactionaries, who are now gathering force, use the absence of adequate intellectual and moral organization in the newer type of school as proof not only of the need of organization, but to identify any and every kind of organization with that instituted before the rise of experimental science. Failure to develop a conception of

organization upon the empirical and experimental basis gives reactionaries a too easy victory.

Dewey realized the need for experimentation, evidence and a well-reasoned argument if progressive schools were to take a place of prominence in American education. I can’t help feeling we’ve failed to heed that warning.