As I work my way through Duckworth, I’m tempted to temporarily change the name of this blog to Reading So You Don’t Have To.

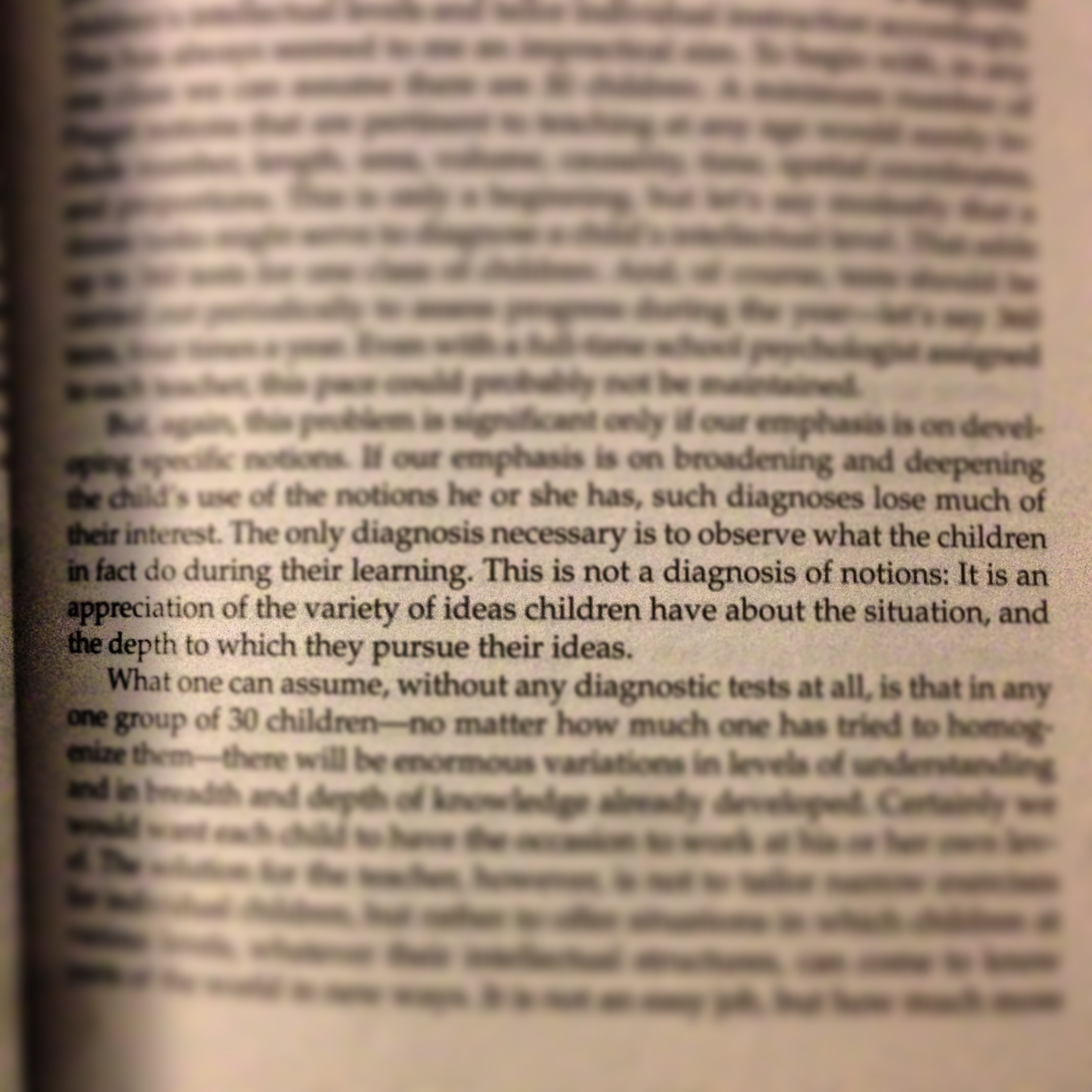

I threw the picture below up on instagram as I was reading last night, and feel like it needs a more prominent display:

My comment attached to the photo was something along the lines of this way of thinking being the only thing I needed to guide my thinking on assessment. That stands. As I continue exploring The Having of Wonderful Ideas, Duckworth is pushing my thinking on assessment even more. Actually, she’s not pushing my thinking so much as putting thoughts I’ve had before into better prose than I’ve yet managed.

It occurred to me, then, that of all the virtues related to intellectual functioning, the most passive is the virtue of knowing the right answer. Knowing the right answer requires no decisions, carries no risks, and makes no demands. It is automatic. It is thoughtless.

This past semester, for the quantitative methods course I was taking, we used a textbook of dubious pedagogy. At the end of each section, though, were some practice problems of the type I remember from my math textbooks of my youth.

Because statistics isn’t exactly where my innate intelligences lie, I found myself frequently stopping to attempt the practice problems. I was curious about these new ideas and this mostly new language of statistical reasoning. I filled large pieces of chart paper with my thinking on these problems with arrows and borderlines to delineate where one thought took a break and moved on to be another thought.

Not always did I arrive at the right answer. What I found, and what surprised me, was the sense of joy and accomplishment I felt when I had an answer and could explain those with whom I studied how I got to that answer. When the answer was wrong, being able to hold up the path I’d taken to reach it somehow took the sting out of its wrongness.

I wouldn’t have paused to appreciate and “meet” the thinking necessary to solve those problems if I simply knew the right answer. If it had been automatic and thoughtless as Duckworth describes, it also would have been a hollow victory if it had been any victory at all.