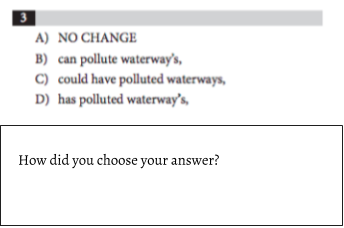

We will, at a later date, examine me railing against test preparation. For today, though, let’s take a look at the problem below.

It is not unlike a problem a well-meaning teacher might put in front of their students. Because exposure/preparation/familiarity. Our well-meaning teacher would take this or something like it from a released bank of items on Standardized Exam Ultra and give it to their students to complete. Why not? The items are aligned to standards, the students will see things like this when they take the real Standardized Exam Ultra, so let’s get them started.

Pedagogy aside (and it’s quite difficult not to go off that way), a completed and scored set of these practice items would give the teacher little to no useful information by which he could shift his practice.

Let’s say 90 percent of the class misses question three. What would scoring this question tell our teacher? Well, it would tell him, in a class of 30 students, 27 got the question wrong. What he’d be likely to claim is this shows his students don’t understand verb tenses, commas, and apostrophes. That’s quite a bit to fit into a single question. In reality, there are at least 27 different paths each of these incorrect students could have taken to reaching the wrong answer. Getting this question wrong only informs instruction insofar as our teacher was wondering whether students got it wrong or right.

If our teacher insists on using this form of assessment, I’d point to a few easy tweaks that would provide greater clarity while increasing the cognitive load on students. I’d even go so far as to claim these tweaks would increase the likelihood of the students arriving at the correct answer.

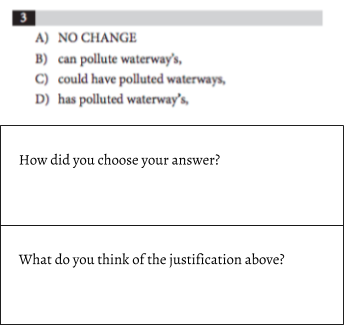

My first alteration is to include a space under each question asking students how they reached the answer they chose. This reveals the paths students took not only to incorrect answers, but correct answers as well. Suddenly, our teacher is able to better understand process. It also moves student reflection into the assessment itself. Rather than asking students why they missed a problem post hoc, we are building a mechanism for students to consider the why of their choices in the moment. Here is the first place I’d argue our group of 27 is more likely to shrink as students pause to think about what they’re doing in ways exercises like these don’t naturally demand. We even put value on answers of “I don’t know.”

What if the shift above isn’t the only move we make? What if we add another space for feedback. This time, though, our students have passed their papers to another classmate and our teacher has asked each classmate to look at the answer and justification of her peer and then reply with her thoughts on the justification? At this point, we’ve begun a conversation, if small, where our students are no longer looking at the answers, but looking at the reasoning and asking if they arrived anywhere worth going.

Think, then, of the information our teacher is working with when he collects these papers. Rather than simply knowing if a given student got a question correct or incorrect, he now also knows how they got there and has given all the class an opportunity to chime in on that thinking at the same time.

The next day, he might pull together students who took similar approaches to reaching the incorrect answer and offer some targeted instruction in correcting their missteps. He might not point out the errors, but put our three correct students in a group with 9 other peers and have them work in small groups to consider how they answered and why they made the choices they did.

It is conceivable our class might grow frustrated with our teacher’s lack of simply telling the correct answer. This is good. I’m assuming these students have computers disguised as phones in their pockets and bookbags. When the discussion reaches its highest frustration, our teacher might say, “Okay, see if you can find help online.”

Here, we’ve taken something boring and inauthentic and built a community around it. We’ve manufactured value to something that originally would have told us if students picked the correct letter or the incorrect letter. While this is not preferable to some authentic, contextualized tasks that would also lead students to practice these skills, it is certainly better than we found it.