Give a year. Change the world.

– City Year

How about we don’t cut full-day kindergarten?

Instead, what if we saved money, innovated the system and began a trend of civic responsibility for young adults in Philadelphia that could serve as the national model.

I’m as big a fan of scare tactics as the next person, but what if the School District of Philadelphia worked to look more like a leader in the time of fiscal crisis, rather than a college freshman signing up for every credit card offer to arrive in the mail?

Cutting half-day kindergarten is a bad idea. It sounds inherently bad when you say it aloud to those with no obvious ties to education.

Then add to that to the Philadelphia Inquirer’s report that we know full-day kindergarten is better:

Research has shown that children in full-day kindergarten demonstrated 40 percent greater proficiency in language skills than half-day kids, said Walter Gilliam, an expert on early-childhood education at the Yale University School of Medicine.

Combining clinical evidence with that feeling deep in your gut should be all you need to realize cutting full-day kindergarten is a bad idea.

This still leaves the shortfall of $51 million as a result of Gov. Corbett’s elimination of a $254 million blacken grant.

Here’s where the innovation comes in.

We cut Grade 12.

To those seniors who have earned enough credits to graduate and/or passed the state standardized test, we allow for the opting out of G12.

Though I couldn’t locate exact numbers by grade, the School District of Philadelphia reports 44,773 students in its high schools.

According to School Matters, SDP has a total per pupil expenditure of $12,738.

Now, if 5,000 of the roughly 45,000 high school students in Philadelphia opted out of their senior year, it would save the district $63,690,000 – almost $12.7 million more than the block grant cuts.

I get that the math is hypothetical, but bear with me.

Not every student is ready for college at the end of their senior year. Even fewer will be ready at the end of their junior years.

Enter the gap year.

Shown to provide students will helpful life experiences as well as a sense of direction once they enter college, a gap year between high school and college would benefit Philadelphia students.

Rather than setting students free to wander aimlessly for that year, the SDP could partner with AmeriCorps, City Year and other organizations to help place Philadelphia graduates around the city in jobs that will invest their time in improving Philadelphia.

The standard City Year stipend would apply, though I’m certain City Year hasn’t the budget for a sudden influx of volunteers.

The SDP would need to show a commitment to sustainable change and invest the money saved by the opt-out program into helping to pay for volunteer stipends.

Ideally, those same graduates would be placed in kindergarten classrooms around the city, helping to reduce student:teacher ratios, providing successful role models and perhaps inspiring more students to move into the teaching profession.

Once students completed their one-year commitment, they would be eligible for the AmeriCorp Education Award to help pay for college tuition.

The idea is admittedly imperfect.

It is not, however, impossible.

It could save full-day kindergarten, reduce costs to the school district, move graduates to invest their time in their city and help lessen the cost of college for Philadelphia graduates.

As an added benefit, such a move could turn the negative press the district’s received for proposing bad policies for children into positive press for creating positive, community-enriching change.

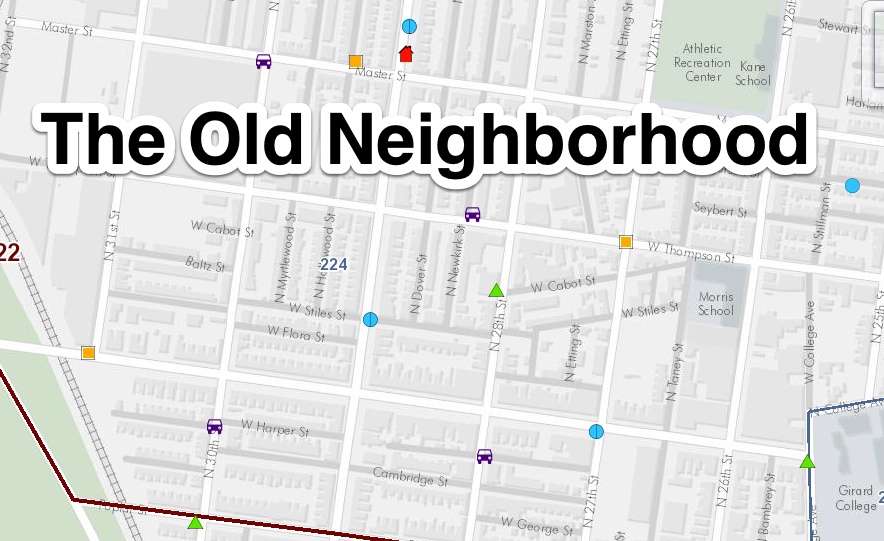

A bit ago, the City of Philadelphia updated its city map to include crime reports by location. Click on the map, zoom in, and you can see who’s been breaking the law near your house.

A bit ago, the City of Philadelphia updated its city map to include crime reports by location. Click on the map, zoom in, and you can see who’s been breaking the law near your house.