An education with inquiry as it’s goal beats an education with mastery as it’s goal every time.

I didn’t realize this is how I feel until a friend asked about the role of mastery at SLA.

Here’s why.

Mastery takes as it’s goal a finished target. This might not always be its intent, but it is the implication whenever we say the goal is getting a student to the point where they or we can say they have “mastered” some content or skill. Such a goal does not invite a logical next step.

Contrastingly, inquiry takes as its goal a continuing cycle of attempting to find things out. Questions beget questions, which beget questions.

If we are asking good questions, our students are going to examine the work they are doing and the answers (partial or whole) they find will lead to the generation of ideas that require more questions be answered before an issue be set aside as satisfactorily answered for the moment.

Some questions, lead to mastery mindset rather than a cycle of inquiry.

If the professional learning modules we are building in my district to help teachers consider and plan for teaching and learning in a 1:1 environment, I am attempting to thoughtfully craft essential questions for each one with avoiding a mastery mindset as one of my goals.

In the module investigating Internet wellness and digital citizenship in middle schools, one question reads, “What is a teacher’s role in helping students consider digital wellness?”

Whatever their initial thinking, a teacher grappling with this question will continue to evolve the answer throughout his career.

“How does a teacher block a website?” Doesn’t invite the same questioning. A skill is learned, and the content mastered. What’s more, when the process changes (as these things inevitably do), a mastery mindset invites a presupposition that the learning was taken care of the first go ’round.

Mastery makes sense as a tool for inquiry. In considering the biological answers to the essential question, “Who am I?” An SLA ninth grader will likely need to master some pieces of proper lab technique or working with the scientific method in the service of their questioning.

As questions become more detailed and the topics more complex, even that mastery will need refinement in hopes of more exact questions.

Mastery offers a waypost of certainty in what can start to feel like an endless cycle of inquiry. For students who frustrate easily, this can be a relief, a respite that allows them to say, “I don’t have the answers I seek, and I know this for now.”

Inquiry with moments of mastery is an invitation to greater discovery founded in growing abilities.

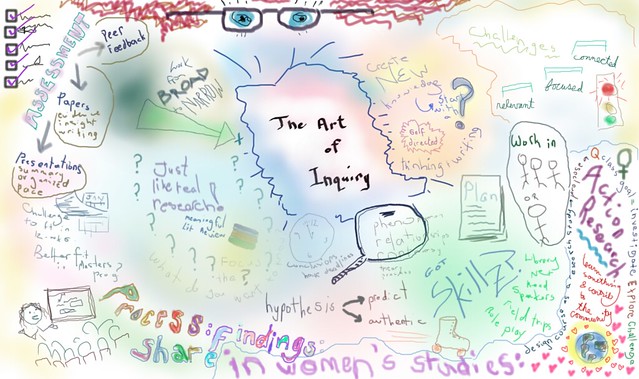

Photo via Candace Nast