I’ve been taking notes in my iPad quite a bit lately. It’s the one device that always seems to make it into my bag. Sometimes, I’m typing – but not always.

I’m a doodler from way back, and my notes tend to be all over a page when I use a pad of paper or a physical notebook. I’ve got boxes and arrows and squiggles. If you want an idea of how my brain organizes information, look at my notepad.

Typing notes doesn’t do that for me. It requires lines and linear thinking that just don’t mesh with how my brain wants to organize ideas on a page. That’s not how I hear them and it’s not how I catalog them in my thinking.

So, I’ve been writing. If you’ve ever tried to write on a tablet with your finger, you know that’s an easy way to start hating using a tablet. Unless you’ve razor-sharp, pointy fingers like Gollum, hand writing on a tablet isn’t at all like your, well, handwriting.

Instead of embracing the frustration, I’ve worked my way through a series of styli for tablets and settled on the JotPro. Instead if the foam or rubber tip of other choices in the market, the JotPro uses a tiny plastic disk attached via a ball bearing to help you make your marks. It is the closest I’ve come to something like a pen on the tablet and I like it.

Except.

It makes a sound. I’m a printer by practice, largely owing to my second-class left-handed status. I was the only one in my class with this particular affliction in second grade when we were learning cursive, so I got about a fifth of hue he instruction and it was backwards.

So, I print.

When using a plastic plate on a glass screen, though, this can mean I make some noise. Printing, for me, with the JotPro sounds like I’ve brought some tinkering elf from Santa’s workshop to the meeting, and he’s building a tiny house. It’s a distraction.

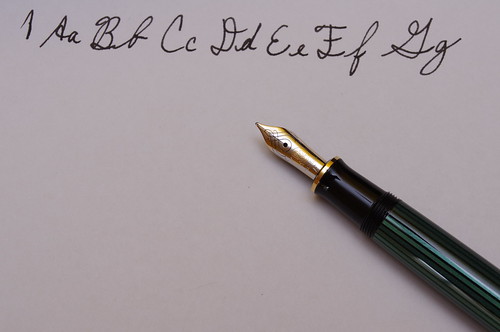

About two weeks ago, I switched from printing. I reluctantly started writing in script. It meant the stylus glided across the screen with only intermittent taps. The elf was sent packing. I’ve not regularly used cursive since…I can’t actually remember.

Now, I’m using it whenever I take notes. Slowly, I’m remembering how to connect all the letters. I still pause longer than I’d like when remembering how, exactly, to form the capital “G,” but I’m on my way.

Lately, in many of the conversations I’ve had in our schools around the district’s plans to put iPads in the hands almost every student, there has been much gnashing of teeth about the future of handwriting and cursive instruction. Those lamenting the possible death of cursive speak of it as though it is a piece of our humanity and not a tool developed for a purpose long forgotten.

I haven’t cared. If the goal is communication, I don’t much care the tool so long as messages are effectively sent and received.

These last two weeks have me thinking a little differently. Perhaps cursive has a place in the modern world. Perhaps it is the tool these new tools were accidentally built for (accidentally).

Cursive isn’t inherent to our becoming whatever the better versions of ourselves might be. It’s possible, however, that cursive might find a renewed purpose in helping us interact with the things we make and the capturing of the ideas that surround us.