Having kids write is important.

Shocking, right?

According to a April 2008 report from the Pew Internet & American Life Project, “Eighty-six percent of teens believe good writing is important to success in life — some 56% describe it as essential and another 30% describe it as important.”

It’s nice when the kids are on our side.

Parents are on our side as well – “Eighty-six percent of teens believe good writing is important to success in life — some 56% describe it as essential and another 30% describe it as important.”

Unfortunately, the kids say our writing instruction is not alright.

“Overall, 82% of teens feel that additional in-class writing time would improve their writing abilities and 78% feel the same way about their teachers using computer-based writing tools.”

I’m trying to work on this.

Aside from the various “bigger” writing projects I ask of students, I’m a huge proponent of journaling.

My journaling practice has evolved over time. It started as I was taught to journal by Mrs. Haake; a prompt was on the board and they responded to it.

Turns out, the tools at my disposal give me more options.

Here are the frequent options:

- Use the picture for inspiration (always an image pulled from creative commons-licensed flickr archives).

- Listen to the song on repeat for inspiration (generally connected, at least tacitly, to whatever we’re reading or discussing in class).

- Watch this video (a few times) and respond.

- Respond to this quotation.

- Free write.

Variations, of course, exist.

The last option is universally on the table. My students come to me from somewhere. It’s easy to forget.

Allowing freewriting allows them to unpack whatever they carry with them into the room.

Journaling can be drawing, journaling can be poetry, journaling can be lists.

The rules:

- Write.

- Don’t think.

- Write.

I don’t read the journals. Scratch that, I don’t make sharing journal entries compulsory. If a student wants to, he or she leaves his journal in a designated location and I read only the last entry. I promise them that’s all I’ll read. If they trust me, they’ll share. If they don’t, they won’t. If they don’t, I work harder.

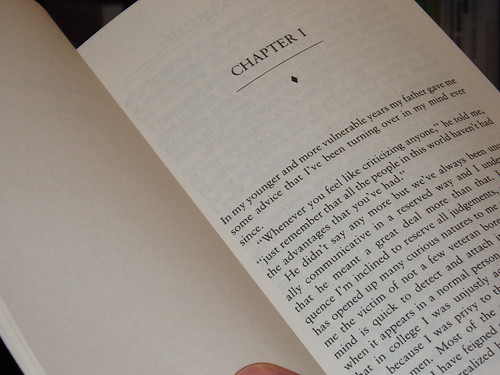

Here is today’s prompt:

One final finding:

Teens who enjoy their school writing more are more likely to engage in creative writing at school compared with teens who report very little enjoyment of school writing (81% vs. 69%). In our focus groups, teens report being motivated to write by relevant, interesting, self-selected topics, and attention and feedback from engaged adults who challenged them.

So, choice, relevance and discussion. Shocking, right?