Pulled together a group of teachers last school year just after things wrapped up for them. Middle and high school English teacher folks from around our district who had answered a call to help us design our new secondary English language arts curriculum were assembled in one of our unaffecting conference rooms.

We’d talked through some of the big pieces, overviewed processes, and were ready to build something practical – something foundational.

I broke the teachers into groups, each with the same charge – use your time, your chart paper, and your collective knowledge to come up with grade-level essential questions worthy of guiding a year’s worth of ELA learning in each grade from 6-12.

The teams scattered, most of them choosing to find places in the grass of the building’s ho hum lawn. Putting back on the familiar suit of habits when I was teaching middle and high schoolers, I began to circulate between the groups. Attempting to be observant and unobtrusive, I stayed with each group until I felt the moment when someone looked to me as though I’d stopped by to supply the “right” answer. Then, I excused myself and made my way to the next group.

As team a team started to get to a draft they felt was stable and worthy of sharing, I begged off being presented to and gave them their next direction. “Great, see that team over there? Go combine your team with theirs, take turns sharing drafts and combine your lists into one.” Eventually, they’d become two groups, representing separate halves of the design team – both mixed with middle and high school teachers, honors and general ed, AP and college prep.

We came back to the conference room, and I put the chart paper with the two teams’ drafts up on the wall. “Okay, now we need to combine these into one draft. What do you notice that can help us with our work?” They set in, talking, pointing out, what if-ing. We moved things into an almost working draft, and I spelled the room for lunch. While they were gone, my colleagues and I took a look at what we’d wrought and made some minor tweaks.

After lunch, I pitched our edits to the team, and they consented to the moves. What had emerged – and I cannot emphasize strongly enough how unlikely we could have made it so elegant if we’d tried – was a series of three themes that cycle twice from sixth to eleventh grade with accompanying essential questions. And, then, having looked at those themes through multiple lenses, we drafted a capstone twelfth-grade theme and essential question that lends itself nicely to an attempt to synthesize those three themes.

G6 – G12 Grade-Level Draft Essential Questions

- G6: Communities: Understanding changing communities: What is community?

- G7: Identities: Redefining identity and values in the face of struggle: Who am I?

- G8: Culture: Determining courage and cowardice in the real world: What is culture?

- G9: Communities: Understanding others’ perspectives: How do we build community?

- G10: Identities: Building resilience and using your voice: How can my voice be used?

- G11: Cultures: Deciding who you want to be: How to morality and ethics shape the individual?

- G12: Interdependence: Connecting with the world: How do I want to impact the world?

A few things strike me as I look back at these questions almost five months later:

First, they hang together. If you were to look across our current curricular resources, each unit or module is complete unto itself. Look for a larger thematic or spiraled link, and you’d find none. Imagine what it must be to be a student moving through our system. The ideas of your sixth-grade ELA class only connecting to seventh or eighth grade only by chance. And connecting to your final years’ experiences in high school? No, certainly not.

“Those questions outside your space, they’re great. I mean, you could really think on those for a good long time.”

Also, they they were drafted by teachers representing almost every secondary school in our district. They were literally asked to come up with the big ideas they might ask our students to play with and consider as readers, writers, speakers, listeners, and thinkers; and they came up with some pretty good ones. These questions, along with their quarterly sub-questions hang on chart paper outside my office. A few weeks ago, our district CIO leaned over in a meeting and said, “Those questions outside your space, they’re great. I mean, you could really think on those for a good long time.” I agreed and explained how they are serving our project. “That’s great!” he replied, “Do you have them typed up somewhere that you could share them with me? I really do love them.” I assured him I’d send them his way.

This raises the element I think I like most about these questions – they are hopeful. And, if not hopeful, then at least loaded with possibility. I’d like to think that comes from the fact they were born of dedicated teachers sitting together, collaborating in the sun, noodling over the best they might do for their students. Either way, they are a long way from “This is when I teach Book X” or “This is my dystopia unit”. So many texts will help our students winnow their ways to answering these questions, and those answers will likely not be well served by activities that ask students “list the important characters in each chapter” or other such drilling that waves at the coast of maturing as literate citizens, but never quite makes it ashore.

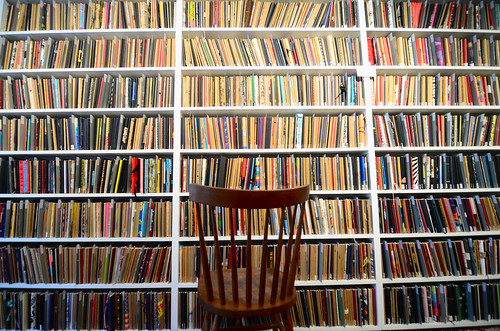

“Do me a favor,” I say, “and close your eyes. I’m going to ask you to visualize something. If I told you you’re visiting a school with a healthy culture of reading and writing, I want to you visit it in your imagination. Start with the lobby or entryway. Notice everything you see and hear as you walk through.”

“Do me a favor,” I say, “and close your eyes. I’m going to ask you to visualize something. If I told you you’re visiting a school with a healthy culture of reading and writing, I want to you visit it in your imagination. Start with the lobby or entryway. Notice everything you see and hear as you walk through.”